NDT Book 2020

NDT Book 2020

Results 1947-2019

Results 2010-2019

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Ken Strange. Ken was a mentor, a friend, and one of the most brilliant debate minds in the history of the activity. He built a culture of excellence, not just as a measure of success, but as a way of life. I am forever thankful that I decided to spend ‘a year, maybe two’ working for him. Fifteen years later, and he’s still, forever, the boss.

Introduction

As the decade comes to a close, it inspires us to look back on the time that has passed. The mere fact of a year that ends in zero doesn’t mean anything by itself, but these momentary pauses are helpful even if the timing is arbitrary. It’s often difficult to see the forest for the trees when we’re in the midst of events, so these pauses for reflection serve an important purpose.

I was lucky enough to begin my college debate career in 1999-2000, which meant that I encountered the newest edition of Bill Southworth’s NDT book in my very first year. I was too young to really understand the history, much less my own place within it. Now, two decades later, I’m still not sure I’m able to fully grasp the scope of that history. Nevertheless, I have agreed to take on the monumental task of continuing this wonderful project. I can only hope that I do some justice to all of Bill’s work over the years, and provide a document that will inspire the current generation to reflect on its own place within our rich history.

On the whole, I’ve largely chosen to follow Bill’s model for the book. This is an update on the existing model, not a new approach to the topic. We will still explore the results from the decade—speakers, preliminary records, individual wins, team participation, etc. We’ll also continue with Bill’s tradition of examining the Best of the Decade. There is only one big change, which you will already have noticed: the NDT Book has entered the 21st century and gone digital. Hopefully this will make distribution of the material easier, and allow for more widespread consumption. There is so much history buried in the records—so many stories waiting to be told. I can’t hope to unearth them all here, but by a durable electronic version of this book should provide a stable framework into which others can start to fill in the gaps.

NDT Winners: 2010-2019

|

Year |

Team |

School NDT wins |

Most recent win |

|

2010 |

MSU (Lanning/Wunderlich) |

3 |

2006 |

|

2011 |

Northwestern (Fisher/Spies) |

14 |

2005 |

|

2012 |

Georgetown (Arsht/Markoff) |

3 |

1992 |

|

2013 |

Emporia (Smith/Wash) |

1 |

n/a |

|

2014 |

Georgetown (Arsht/Markoff) |

4 |

2012 |

|

2015 |

Northwestern (Miles/Vellayappan) |

15 |

2011 |

|

2016 |

Harvard (Herman/Sanjeev) |

7 |

1990 |

|

2017 |

Rutgers-Newark (Murphy/Nave) |

1 |

n/a |

|

2018 |

Kansas (Katz/Robinson) |

6 |

2009 |

|

2019 |

Kentucky (Bannister/Trufanov) |

2 |

1986 |

Copeland Winners: 2010-2019

|

2010 |

Emory |

Weil/Inamullah |

|

2011 |

Emory |

Weil/Inamullah |

|

2012 |

Northwestern |

Beiermeister/Kirshon |

|

2013 |

Georgetown |

Arsht/Markoff |

|

2014 |

Northwestern |

Miles/Vellayappan |

|

2015 |

Northwestern |

Miles/Vellayappan |

|

2016 |

Harvard |

Herman/Sanjeev |

|

2017 |

Harvard |

Midha/Sanjeev |

|

2018 |

Kansas |

Katz/Robinson |

|

2019 |

Kentucky |

Bannister/Trufanov |

This decade saw nine different teams take the ten titles, with only Georgetown Arsht/Markoff as repeat victors. In the Copeland race, there was far less diversity among winners, with Emory Weil/Inamullah and Northwestern Miles/Vellayappan each taking back-to-back titles. Harvard’s Sanjeev also won consecutive Copelands with different partners.

There was some overlap between Copeland winners and the eventual tournament champion, with 2015 (Miles/Vellayappan), 2016 (Herman/Sanjeev), 2018 (Katz/Robinson) and 2019 (Bannister/Trufanov) seeing teams take home both awards. Strangely, Georgetown Arsht/Markoff won the tournament twice and also won a Copeland award, but never both at the same time.

Northwestern’s two wins extended their record number of NDT titles to 15. Harvard claimed a clear second place in all-time victories with their 7th title, while Kansas joined Dartmouth in third place all-time by claiming their 6th.

Ten years ago, no team had ever won both the NDT and the CEDA National tournament. Two managed it this decade, first Emporia in 2013, followed by Rutgers-Newark in 2017.

Later sections will comb through the results of the decade—and across the whole scope of NDT history—in a lot more detail. But before embarking on that project, I want to take a moment and identify a few major themes that defined the 2010s in college debate. These will receive more discussion throughout the various pages of the book, but it’s worth taking a moment to reflect on the big picture developments of the community before diving into the details.

First, the 2010s was the decade when debate went paperless. This process was already underway at the start of the decade, but quickly swept across the country. Within just a few years, the entire infrastructure of tournament travel changed. Gone are tubs, as well as the never-ending hassle of negotiating their transportation with airlines. Gone are the printers, and printer jams. Debate rounds now take place entirely on computers via speech docs. It hasn’t been a perfectly seamless transition. Certainly, those of us old enough to remember what things used to be like are often grumpy about the state of flowing. Then again, when have the old-timers not been grumpy about the present state of flowing. But on the whole the change came with far less disruption than many anticipated.

The big question going forward is whether the increasing digitalization of the activity will continue, and whether this might provide alternatives to in-person tournaments, or at least an incentive to finally push the balance back toward regionalization and away from nationalization of the activity. The 2010s saw some meaningful activity in that direction, but it the ‘major’ tournaments which feed into the NDT remains largely the same as in previous generations.

The second major theme of the 2010s concerns the substance of debates themselves. This decade saw major developments in the longstanding conservations within the activity about objectives, values, and the very idea of what debate is for. At times, it felt like debate was really two parallel activities. One concerned with traditional policy questions, disadvantages and counterplans, and the occasional ‘old school’ critique; the other concerned with tactics of political engagement, identity politics, and forthright challenges to the apparatus of policy itself. This was not a new phenomenon, but the extent to which the activity seemed to splinter has been relatively unprecedented, with perhaps the NDT/CEDA split as the only most apposite parallel.

The arguments have also stepped outside of the debate rounds themselves to focus on the way structures of the activity promote and sustain particular modes of engagement. We have seen in recent years significant pushback against Mutual Preference Judging, which is regarded by some as a tool for excluding perspectives and insulating (policy) teams from the obligation to assess the broader implications of their arguments. These arguments have also attached themselves to the previous topic of how (and where) tournaments are held. The community has only just begun to seriously reckon with the indelibility of the tournament calendar.

A third important theme: the increased prominence and success of women, particularly women of color. Women and people of color have mostly been absent from previous iterations of this book. That has sadly reflected the reality of college debate as an activity, and of the NDT in particular. Going back to the original NDT in 1947, the field contained just two women. For the following decades, many national tournaments separated the genders. West Point did not admit female cadets until 1976, and the early NDT hosts explicitly forbid entrants from women-only institutions. There was obviously no such restriction on all-male schools. Through the 2006 NDT, only 14 women had ever appeared in the final round. In 2007, three of the four finalists were women, with Emory’s team of Hamraie and Hoehn becoming the first all-woman team to win the title.

When Stephanie Spies earned the top speaker award in 2011, she was only the third woman in NDT history to take that title, following Patricia Stallings (Houston 1957) and Gloria Cabada (Wake Forest 1988). Compared to that historical imbalance, the 2010s were far more balanced.

To be clear, things still have hardly equalized, or come anywhere close to it, really. We still remain far, far from the ideal, and there is a lot of work still to do. But for the first time, these end-of-decade rankings include prominent positions for women across many of the categories. The debater of the decade was a woman of color, with several other women in the top 10. The judge of the decade was a woman, with two black women also in the top five. In addition to being rated the third best judge of the decade, Amber Kelsie was also assessed as the second-best coach. Just over a quarter of the final round participants in the 2010s were women, up a huge degree from the previous tally of 6.7%. Women made up close to half of the top and 2nd place speakers. And overall participation levels have increased as well.

These changes may be tied to the shifts in argumentation described above. While some of the most successful women over this decade fall clearly into the camp of ‘traditional’ debate, the expanded scope of advocacy has clearly not been limited to the debate rounds themselves. With powerful voices pressing the case for a form of politics that goes beyond tokenism and ‘diversity,’ the activity itself has also been at least partially reconstituted.

Finally, this decade has also seen powerful conversations about openness and accessibility. The leading voices in the national organizations have been pressed to account for their practices, to attend to sexual abuse and harassment, to respond to their place within exclusive political systems. These have not been easy conversations, but they have been necessary. It remains very much an ongoing process of contestation and limited resolution.

These changes within the activity have also played out within the NDT itself. The decade saw some very traditional tournament winners, with Northwestern, Harvard, and Kansas all among the four most successful schools in NDT history. But we also saw two first time winners—Emporia and Rutgers-Newark. Emporia were long-time NDT veterans, having attended over two dozen times before their win, first as Kansas State Teachers College and then as Emporia. But Rutgers-Newark did not even have a program until 2008. Both Emporia and Rutgers-Newark also broke barriers as the first two teams to win both the CEDA National tournament and the NDT. They were also both ‘non-policy’ competitors, expanding the range of what it was possible to argue, as well as how arguments could be made.

There is perhaps no more fitting way of characterizing the structure of the decade than to note that Emporia’s groundbreaking victory was flanked by two wins from the Georgetown team of Arsht and Markoff—representing one of the most successful schools in NDT history, with argument choices and a debating style that would not have been out of place in many previous eras. This pluralism has not always been comfortable, or sufficient. But for better and for worse, it remains a core feature of the community’s identity as it enters the 2020s.

Postscript: This book was prepared in anticipation of being released simultaneous with the start of the 2020 National Debate Tournament. Sadly, for the first time in its history, the NDT will not occur this year, having been canceled in response to the spread of the Covid-19 coronavirus. Obviously, there are larger problems in the world than the cancellation of a debate tournament, but it is nevertheless bittersweet for all of us who care deeply about debate as an activity. I find myself particularly moved, having just completed this immense project of combing through and collecting the history of the activity and tournament. I was already looking forward to seeing what new names would inscribe themselves into history at this tournament. Now, we are left with nothing but possibilities. I dearly hope that everyone who was denied their chance to shine at this tournament understand how much their pain is felt by those of us watching from near and far. 2020 will forever exist as an asterisk in NDT history. I fervently hope that everyone is able to come back stronger than ever and once again make this the culmination of a year spent working together as a community to advance understanding and political engagement.

The history of the NDT: From West Point to the Internet

Picture It:

Date: Sunday, May 4, 1947

Time: 2:00 PM

Location: United States Military Academy at West Point

The Cullum Memorial Hall

Occasion: The FINAL ROUND of the FIRST NDT

Affirmative: University of Southern California

George Grover & Peter Kerfoot

Negative: Southeastern State College of Oklahoma

Scott Nobles & Gerald Sanders

Result: Negative 3-2

Impact: Intercollegiate debate would never be the same!

In 1986 Glenn R. Capp of Baylor University explained how and why the first National Tournament was born in his book Excellence in Forensics: A Tradition at Baylor University:

“The National Debate Tournament was an instant success largely because of the leadership of the West Point Military Academy in organizing it and because it embodied an idea whose time had come. Until 1947, the national fraternities (Pi Kappa Delta, Delta Sigma Rho, and Tau Kappa Alpha) had held national tournaments that restricted participation to member universities, but there was no organization that cut across existing fraternities to include all universities. I received a letter and questionnaire dated May 27, 1946, from William F. Gorog of the West Point Debating Society which stated in part:

We understand that your institution has been quite active in debating circles during the past few years, and we would appreciate having your opinion on a question which has been discussed recently to great length here at the Academy.

At present there is no all inclusive organization of intercollegiate debating societies, and as a result there has never been a national intercollegiate debate tournament. At present the Academy sponsors an annual tournament with some of the finest teams of the East and Middle West participating. Because of the success of these affairs, our Superintendent, General Taylor, has promised us every support in the organization of a National Tournament with participants representing every part of the United States. This would be a tournament which could at long last determine a National Intercollegiate Debating Championship.

It is our intention to invite the outstanding team from each section of the country. The question at hand at this point is the method of determining the team or teams to represent each district. Dr. Alan Nichols of the University of Southern California has suggested that the nation be divided into districts with a committee of outstanding coaches in each to determine the qualified teams. ” (Pages 140-141)

In his December 1946 issue of The Debater’s Magazine, Egbert Ray Nichols of the University of Redlands, described the progress that Cadet Gorog and his Tournament Committee were making:

“West Point’s National Debate Tournament is going full speed ahead! Backed by an overwhelmingly favorable response to a detailed questionnaire sent to many prominent speech-conscious institutions, the West Point Debating Society has its tournament blueprints in the final stage. The U.S. Military Academy’s debaters, with the aid and encouragement of Major General Maxwell D. Taylor, superintendent of the Academy, are out to make this first venture of this type a blazing success.

Selected on the recommendation of outstanding speech instructors throughout the country, members of the regional committees to choose teams for the tournament have already been notified of their appointment. Three-man boards operating in the districts shown on the accompanying map will nominate the 32 participating schools on the basis of their performance in intercollegiate forensics during the current season.

Any team nominated by a regional committee will be eligible to participate in the tournament, which will consist of five preliminary and four elimination rounds. Plans are now under way to broadcast the final debate.

The custom in the previous invitational tournaments held at West Point will continue into the National: There will be no entrance fees, and accommodations and meals will be furnished free of charge to all contestants.

Army’s tournament, bringing together the outstanding debaters from all sections of the country, will undoubtedly prove a potent stimulus to American forensics after the inevitable decline of the war years.” (Page 263)

In the March 1947 issue of The Debaters Magazine Dr. Nichols described the details of the National Tournament the West Point cadets were planning:

“On the basis of a survey made early this year, outstanding speech coaches have been chosen in each of the seven districts to represent the National Tournament Committee in selecting qualified teams. It is felt that coaches in the regions themselves will be in a much better position to choose the representatives than any group located in one part of the country. The method of choice is extremely flexible, depending upon the facilities at the disposal of the various district committees. In most cases, sufficient tournament facilities are already available to provide the committeemen with enough information to determine the strongest teams. It has been requested that all selections be made and submitted to Tournament Headquarters by March 14, 1947. The names of two alternate teams in addition to the district quota will also be included in the selections.

The Regional Committees have been organized as follows:

Region No. 1—Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah.

Alan Nichols, USC; E.R. Nichols, Univ. of Redlands; W. Arthur Cable, Univ. of Arizona.

Region No. 2—Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington, Wyoming.

W.M. Veatch, State College of Washington; Herbert Rae, Willamette Univ.; John Leary,

Gonzaga University.

Region No. 3—Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas.

R.S. Weatherell, TCU; Glenn R. Capp, Baylor Univ.; H. H. Anderson, Oklahoma A&M.

Region No. 4—Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Minnesota, Nebraska, North & South Dakota.

Thorel B. Fest, Univ. of Colorado; Forest Rose, S.E. Missouri Teacher’s College.

Region No. 5—Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin.

- Garber Drushal, College of Wooster; Glenn Mills, Northwestern Univ.; Leonard Sommer,

Univ. of Notre Dame.

Region No. 6—Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North & South Carolina, Tennessee,

Virginia, West Virginia.

Wayne C. Eubank, Univ. of Florida; Albert Keiser, Lenoir-Rhyne College; J.T. Daniel, Univ.

of Alabama.

Region No. 7—Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey,

New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont.

J.F. O’Brien, Penn State College; Brooks Quimby, Bates College; John Chester Adams, Yale Univ.

The regional quotas for team representation is as follows:

Region 1, 4 teams, 2 alternate teams.

Region 2, 3 teams, 2 alternate teams.

Region 3, 4 teams, 2 alternate teams.

Region 4, 5 teams, 2 alternate teams.

Region 5, 6 teams, 2 alternate teams.

Region 6, 4 teams, 2 alternate teams.

Region 7, 6 teams, 2 alternate teams.

Teams will consist of two debaters and will be limited to undergraduate students. Each team will come prepared to debate both sides of the National Question. RESOLVED: That labor should be given a direct share in the management of industry. In order to provide adequate judging personnel, one qualified judge will accompany each team.

There will be a total of nine rounds of debate over a period of three days. The first five rounds will be judged on both a “win or lose” basis and on a point basis. After five rounds of debate (with all teams participating), the sixteen strongest teams will begin an elimination tournament. At least three judges will be assigned for each elimination round. “(Pages 61-62).

National Tournament Schedule

Friday, May 2, 1947

10:30 AM Final arrival time and registration

11:00 Orientation meeting and drawing for position

12:00 Dinner

2:00 PM First round of debate

3:30 Second round of debate

6:30 Supper

8:00 Third round of debate

Saturday, May 3

8:30 AM Fourth round of debate

10:00 Fifth round of debate

12:00 Dinner

2:00 PM Sixth (1st Elimination Round 16 teams)

3:30 Seventh round (Quarters. . .8 teams)

6:30 Eighth round (Semi-finals. . .4 teams)

9:15 Movies at War Department Theatre

10:30 Formal Dance

Sunday, May 4th

Sunday morning will be reserved for Chapel Services, Catholic, Jewish, and Protestant Services will be available to all participants.

1:15 PM Banquet at Cullum Memorial Hall

2:00 Final Round of Debate

The original twenty-nine teams at the first NDT:

Southeastern State College, OK. (Scott Nobles & Gerald Sanders) 8-1 First

USC, CA (Potter Kerfoot & George Grover) 5-4 Second

Army, NY (John Lowry & George Dell) 7-1 Third

Notre Dame, IND. (Frank Finn & Tim Kelley) 6-2 Third

Navy, MD (Jack Jones & Robert Miller) 6-1 Quarters

Louisiana College (H.A. Munderup & Chandler Clover) 5-2 Quarters

Northwestern Univ., IL (James McBath & Fred Zeni) 4-3 Quarters

Univ. of Mississippi (Brinkley Morton & Jesse Holleman) 4-3 Quarters

Univ. of Vermont (Leona Felix & Norman Vercoe) 5-1 Octos

Univ. of Virginia (Charles Ide & William Pierce) 4-2 Octos

Augustana College, IL (Harold Brock & John Swenson) 3-3 Octos

Yale Univ., CN (Richard Shapiro & Holt & Westerfield) 3-3 Octos

Rutgers Univ., NJ (Milton Anapol & Donald Yawitz) 3-3 Octos

Wake Forest Univ., NC (Sam Behrends & Henry Huff) 3-3 Octos

Univ. Texas, Austin (Harold Sanders & Jack Skaggs) 3-3 Octos

College of St. Thomas, MN (Thomas Ticen & Martin Haley) 2-4 Octos

Oklahoma Baptist Univ. (Eugene Craighead & Dean Emery) 2-3

Washington State (Dick Downing & Janice Loschen) 2-3

Ohio State (Charles Vernon & William Holleran) 2-3

Wheaton College, IL (Roy Fanoni & David Howard) 2-3

Texas Christian (Charles Matthews & Bob Hearn) 2-3

Univ. of Colorado (Roger Dotens & Robert Polkinhorn) 1-4

Purdue Univ., IND (Archies Colby & Norris Sample) 1-4

Oregon State (Donald Rowland & Donald Dimick) 1-4

Penn State (Peter Giesey & Fred Keisler) 1-4

Gonzaga Univ., WA (Don Shahan & Tom Foley) 1-4

Indiana State Teachers College (Ellis Anderson & Gene Moore) 1-4

Univ. of Utah (Adam Duncan & Wallace Bennett) 1-4

Arizona State (Gene Turner & Howard Thompson) 0-5

Coverage of the NDT

The United States Military Academy, as both sponsor and host of the National Debate Tournament for the first twenty years offered numerous unique advantages. Financially the Army covered many expenses, like banquets, which now must be covered by tournament entry fees. After leaving West Point the AFA assumed sponsorship of the NDT, but its financial contribution was minimal, in 1976 the Ford Foundation came aboard with a small, but significant, yearly contribution that was increased in 1996, but abandoned a few years later as car sales began to decline. However, a big advantage of West Point was its geographic location, just a short distance from the media capital of the world—New York City! Combined with their own prestige they were able to insure significant coverage in the New York Press. However, beginning in 1948 they achieved several publicity coups through the use of radio and a new medium that was gaining popularity—Television!

“We the People” a CBS interview show was the first to have the final round participants as their guests. Radio coverage was apparently rather extensive. Beginning in 1957 the New York Times “Youth Forum” TV program, first on WRCA TV and then WNBC TV, began a ten-year run of hosting the finalists for discussions of the topic they had debated and researched all year. In 1958 “The College News Conference Show” on ABC was added to the list, although it aired from Washington, DC. In 1959 the winners were featured on the Dave Garroway “Today Show” on NBC. In 1961 “GE College Bowl” on WCBS TV was where you could find the NDT finalists being interviewed. By 1962 West Point in cooperation with the National Educational Television/ Radio Network, produced, “The National Debate Tournament at West Point” this show ran until West Point ended its administration of the NDT in 1966.

When the AFA sponsorship began they started publishing a transcript of the Final Round in the American Forensic Association Journal, which became the Argumentation and Advocacy Journal in the Summer of 1988. Following the 1985 final round, John Boaz, former AFA President and JAFA Editor, found transcribing the final round too difficult an endeavor and ended that process. I tried to revive the process when the Post Tournament Book was re-introduced in 1988, but that lasted a few short years, it became obvious that virtually no one could accurately decipher the tapes of current debates.

Obviously, successful teams receive press coverage of their accomplishments on a local level, but national exposure has been quite limited. That is until 2004, when College Sports Television (CSTV) produced an hour-long documentary on the NDT. They met with several teams prior to the tournament and then followed them throughout the event. The ultimate show was quite interesting and insightful for any viewer. They followed a similar procedure for 2005 and 2006 NDT’s. Prior to the 2006 NDT Liberty University received national coverage with two glowing articles. One in Newsweek (147 no6 56 F 6 2006, “Thrust and Christ”) and the other in the New York Times Magazine (March 19, 2006; “Ministers of Debate”) Both articles focused on the conservative religious emphasis of Liberty and the political implications of such a successful program, not much about the NDT. Unfortunately, not all publicity is good, a few months after the 2008 CEDA National Tournament some explosive video made its way to YouTube and ultimately to CNN; it showed a bitter argument quickly getting out of control and resulting in a very visible mooning by one coach. The ensuing media uproar cost one person his job and the elimination of an entire program.

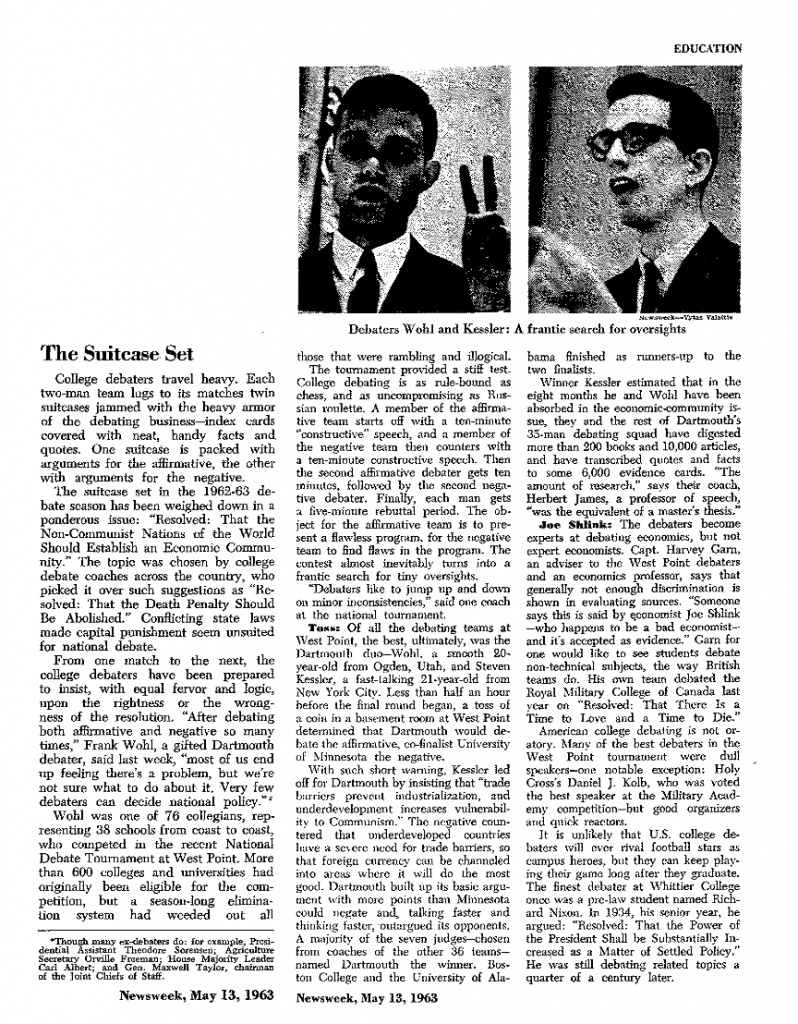

In the “good old days” the media viewed debate much differently, as found in this 1963 Newsweek article analyzing the Dartmouth team who had just captured the National Championship.

Tournament Hosts

West Point hosted the National Championships for twenty years. Suddenly during the 1966 tournament” Colonel Lincoln, the West Point Tournament Director, met with the district chairs and advised them that at the tournament banquet he would announce the Military Academy’s decision to discontinue hosting the NDT.” George Ziegelmueller of Wayne State University, Anabel Hagood of the University of Alabama and Herb James of Dartmouth formed a committee to discuss the possibility of West Point hosting the event for one more year while plans were made for the transition. “The Superintendent explained that because of the United States’ growing involvement in the war in Southeast Asia the number of men admitted to the Academy was scheduled to increase and that both space and money were in short supply. In a reappraisal of the mission of the Academy, the sponsorship of the NDT was not judged to be a high priority. . .he refused to approve an extension.” The District Chairs then requested of Prof. Ziegelmueller that, as the then President of the American Forensic Association, he take to the AFA the possibility of that organization sponsoring the National Championship. George was busy coaching his own team at the tournament (they would later place second) but when contacted he agreed and the process was begun. (Argumentation & Advocacy Journal, Vo. 32, No. 3, Winter 1996)

Departure from West Point changed the tournament considerably. The Military Academy had provided a rather unique atmosphere and a rich tradition that would be hard to replace. The first non-West Point host was the University of Chicago in combination with Northwestern University and was generally regarded as a success.

The next non-West Point NDT, however, went over less well. As Dr. Southworth wrote:

“It was my first NDT, and what a disaster, both for me, and the tournament. Brooklyn College was the host, but the only housing facility was a local motel that also served as a “brothel.” If there was any doubt about the normal function of this motel it was made clear the first night when many returned to find their baggage outside their rooms and the doors bolted. When Prof. Ziegelmueller confronted the management, he was informed that some rooms were needed to take care of his more shady patrons who wished to rent by the hour. When George introduced Laurence Tribe, then the Harvard debate coach, as the NDT’s legal counsel, the manager became quite cooperative. (Argumentation & Advocacy, Winter 1996, Vol. 32, No. 3, Pg. 146) Unfortunately, Brooklyn, on-balance was not the ideal location. I can remember watching the final round, Wichita vs. Butler in an auditorium which had very little lighting and equally bad acoustics, thus, most of the judges could barely see or hear the debate to even take notes. Suffice to say the University of Northern Illinois was a most welcomed host in 1969.”

Soon enough, though, everyone settled happily into the process of rotating tournament hosts, as reflected in the following list of tournament sites and hosts.

|

YEAR |

SITE |

HOST |

DIRECTOR |

|

1947-1966 |

West Point Military Academy |

||

|

1967 |

University of Chicago |

Richard Lavarnway & Thomas B. McClain |

Stanley G. Rives |

|

1968 |

Brooklyn College |

Charles E. Parkhurst |

Richard D. Rieke |

|

1969 |

Northern Illinois Uni. |

M. Jack Parker |

Rodger Hufford |

|

1970 |

University of Houston |

William English |

David Matheny |

|

1971 |

Macalester College |

W. Scott Nobles |

John C. Lehman |

|

1972 |

University of Utah |

Jack Rhodes |

John C. Lehman |

|

1973 |

U.S. Naval Academy |

Philip Warken |

Merwyn A. Hayes |

|

1974 |

U.S. Air Force Academy |

David Whitlock |

Merwyn A. Hayes |

|

1975 |

University of the Pacific |

Paul Winters |

Michael D. Hazen |

|

1976 |

Boston College |

Daniel M. Rohrer |

Michael D. Hazen |

|

1977 |

Southwest Missouri State Univ. |

Rita Rice Flaningam |

Michael D. Hazen |

|

1978 |

Metropolitan State College, CO |

Gary Holbrook |

Michael D. Hazen |

|

1979 |

University of Kentucky |

J.W. Patterson |

Michael D. Hazen |

|

1980 |

University of Arizona |

Tim A. Browning |

Michael D. Hazen |

|

1981 |

Cal Poly Pomona Univ. |

Robert Charles |

Michael D. Hazen |

|

1982 |

Florida State University |

Marilyn J. Young |

Michael D. Hazen |

|

1983 |

Colorado College |

James A. Johnson |

Michael D. Hazen |

|

1984 |

University of Tennessee |

Russell T. Church |

David Zarefsky |

|

1985 |

Gonzaga University |

Darrell Scott & Joan Archer |

David Zarefsky |

|

1986 |

Dartmouth College |

Herbert L. James |

David Zarefsky |

|

1987 |

Illinois State University |

Arnie Madsen |

David Zarefsky |

|

1988 |

Weber State College |

Randy Scott |

David Zarefsky |

|

1989 |

Miami Univ. of Ohio |

Jack Rhodes |

David Zarefsky |

|

1990 |

West Georgia College |

Chester Gibson |

Al Johnson |

|

1991 |

Trinity University |

Frank Harrison |

Al Johnson |

|

1992 |

Miami Univ. of Ohio |

Jack Rhodes |

Al Johnson |

|

1993 |

Univ. of Northern Iowa |

Bill Henderson |

Donn W. Parson |

|

1994 |

Univ. of Louisville |

Tim Hynes |

Donn W. Parson |

|

1995 |

West Georgia College |

Chester Gibson |

Donn W. Parson |

|

1996 |

Wake Forest Univ. |

Allan D. Louden |

Donn W. Parson |

|

1997 |

Liberty University |

Brett O’Donnell |

Donn W. Parson |

|

1998 |

University of Utah |

Rebecca Bjork |

Donn W. Parson |

|

1999 |

Wayne State Univ. |

George Ziegelmueller |

Donn W. Parson |

|

2000 |

Univ. of Missouri, KC |

Linda Collier |

Donn W. Parson |

|

2001 |

Baylor University |

Karla Leeper |

Donn W. Parson |

|

2002 |

Southwest Missouri State |

John Fritch |

Donn W. Parson |

|

2003 |

Emory University |

Melissa Wade & Bill Newnam |

Donn W. Parson |

|

2004 |

Catholic University |

Ron Bratt |

Donn W. Parson |

|

2005 |

Gonzaga University |

Glen Frappier |

John Fritch |

|

2006 |

Northwestern University |

Scott Deatherage |

John Fritch |

|

2007 |

Westin Convention Center |

Dallas, Texas |

John Fritch |

|

2008 |

Cal State Fullerton |

Jon Bruschke |

John Fritch |

|

2009 |

University of Texas |

Joel Rollins |

John Fritch |

|

2010 |

Cal Berkeley |

Dave Arnett & Greg Achten |

John Fritch |

|

2011 |

UT-Dallas |

Chris Burke |

John Fritch |

|

2012 |

Emory University |

Bill Newnam |

John Fritch |

|

2013 |

Weber State University |

Omar Guevera |

John Fritch |

|

2014 |

Indiana |

Brian Shah-Delong |

John Fritch |

|

2015 |

Iowa |

Paul Bellus |

John Fritch |

|

2016 |

Binghamton |

Joe Schatz |

Sarah Partlow Lefevre |

|

2017 |

Kansas – Edwards Campus |

Scott Harris |

Sarah Partlow Lefevre |

|

2018 |

Wichita State |

Jeffrey Jarman |

Sarah Partlow Lefevre |

|

2019 |

Minnesota |

David Cram Helwich |

Sarah Partlow Lefevre |

Ranking NDT Hosts

Since 1980, Dr. Southworth’s ‘Best of the Decade’ polls have asked for an assessment of the different hosts. Unfortunately, no such survey was taken during the West Point years or for the 1960’s. Only Dartmouth for the 1980s and the Westin Hotel for the 2000s received overwhelming support. In every other decade, there was considerable division among voters over the favorite hosts.

|

BEST NDTs of the 1970s |

||

|

1 |

Metropolitan State College, Denver, Colorado |

1978 |

|

2 |

University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky |

1979 |

|

3 |

U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado |

1974 |

|

4 |

University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah |

1972 |

|

5 |

University of the Pacific, Stockton, California |

1975 |

|

BEST NDTs of the 1980s |

||

|

1 |

Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire |

1986 |

|

2 |

Gonzaga University, Spokane, Washington |

1985 |

|

3 |

University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona |

1980 |

|

4 |

University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee |

1984 |

|

5 |

Cal Poly Pomona, Pomona, California |

1981 |

|

BEST NDTs of the 1990s |

||

|

1 |

Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan |

1999 |

|

2 |

Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina |

1996 |

|

3 |

Liberty University, Lynchburg, Virginia |

1997 |

|

4 |

West Georgia College, Carrollton, Georgia |

1995 |

|

5 |

West Georgia College, Carrollton, Georgia |

1990 |

|

BEST NDTs of the 2000s |

||

|

1 |

Westin Hotel, Dallas, Texas |

2007 |

|

2 |

Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois |

2006 |

|

3 |

Gonzaga University, Spokane, Washington |

2005 |

|

4 |

University of Texas, Austin, Texas |

2009 |

|

5 |

University of Missouri at Kansas City |

2000 |

|

BEST NDTs of the 2010s |

||

|

1 |

Weber State University, Ogden, Utah |

2013 |

|

2 |

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota |

2019 |

|

3 |

University of Kansas Edwards Campus, Overland Park, Kansas |

2017 |

|

4 |

Wichita State University, Wichita, Kansas |

2018 |

|

5 |

University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa |

2015 |

The Best of the Decade: 2010-2019

For the past four decades, Dr. Southworth conducted a poll of coaches. The key questions: who were the best individual debaters? The best teams? The best judges? Which topics were good and which were bad? Which hosts did the best? These questions invite rankings, but more importantly they give us all a chance to reflect on what makes the activity great.

Taking over the project this year, I continued this tradition. In total, I received 41 responses, though not every voter answered every question. The following details the results of those responses.

Outstanding Debater

Kansas’s Quaram Robinson, the overwhelming choice for Debater of the Decade

Voters were asked to “provide a ranked list of the top 10 outstanding debaters of the decade.” Total points are based on 10 points for a 1st place vote, 9 for 2nd, etc.

68 different debaters received votes, including 16 different first place votes.

There was clearly an enormous amount of talent spread widely around over the decade. But there was also a clear standout at the top. Quaram Robinson from Kansas raced out to an early lead in this category and never looked back. Her performance record speaks for itself: with two final round appearances, winning once, a Copeland Award, and 33 NDT debates won (tied for 9th all-time) over her four-year career. The truly incredible thing is that she did all of that with four different partners! As far as I can tell, there is no debater in NDT history who comes remotely close to this level of sustained excellence with a new partner each year.

Taking second place was Andrew Markoff, who finished just one point ahead of Arjun Vellayappan in third. The razor thin margin is perhaps unsurprising, since the two are tied (along with Markoff’s longtime partner Andrew Arsht who came in at #4) for the second-most victories in NDT history, with 38. Moreover, Vellayappan stands alone at the top with an astonishing 13 elimination round victories. He is also notable for being one of two debaters to show up twice on the Outstanding Team list below, first for his partnership with Alex Miles (#10), second for his partnership with Peyton Lee (#12). The other such debater was Hemanth Sanjeev (#8), who appeared first with David Herman and then with Ayush Midha (#17)

Emporia’s record-setting team of Wash (#7) and Smith (#11)—the first team to unite the CEDA and NDT titles—both also appear toward the top of the list, while the team of Murphy and Nave from Rutgers-Newark, who repeated that feat a couple years later follow closely behind at #12 and #14.

Several debaters on this list split significant time with the last decade. Both Stephen Weil and Stephanie Spies only debated for fifteen months during the 2010s, but were so dominant in those years to assert a place on the list.

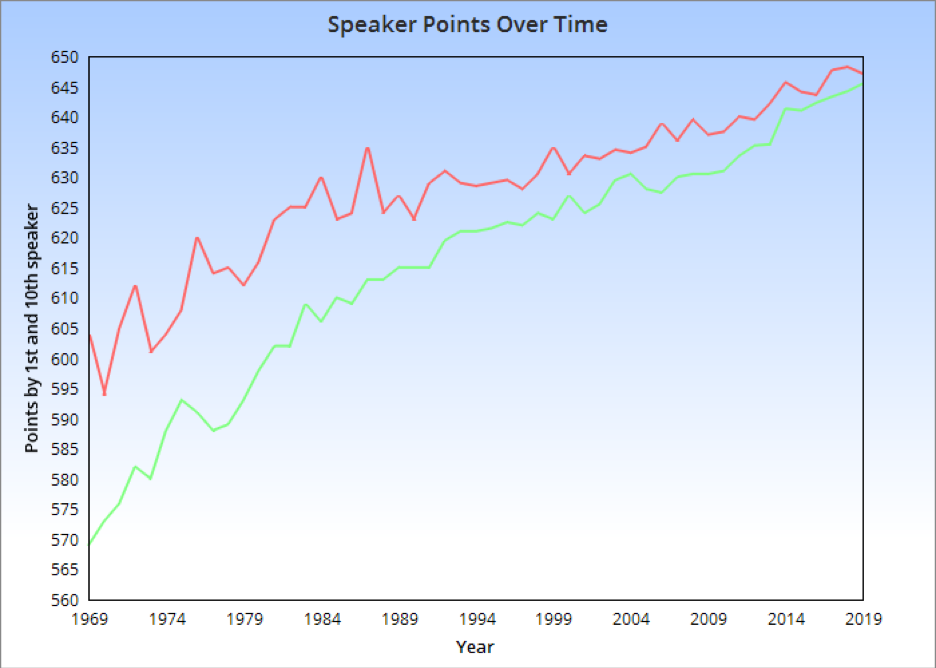

Seven of the ten NDT Top Speakers of the 2010s appear on this list and are noted with an asterisk. However, the top three debaters on this list never managed to earn a Top Speaker award, suggesting that overall acclaim does not necessarily correlate perfectly with speaker points in the round.

| Team | School | Points | 1st Place Votes | ||

| 1 | Quaram Robinson | Kansas | 218 | 6 | |

| 2 | Andrew Markoff | Georgetown | 169 | 4 | |

| 3 | Arjun Vellayappan | Northwestern | 168 | 6 | |

| 4 | Andrew Arsht* | Georgetown | 158 | 1 | |

| 5 | Stephen Weil* | Emory | 152 | 3 | |

| 6 | Stephanie Spies* | Northwestern | 123 | 4 | |

| 7 | Ryan Wash | Emporia | 106 | 4 | |

| 8 | Hemanth Sanjeev | Harvard | 104 | 1 | |

| 9 | Natalie Knez* | Georgetown | 93 | ||

| 10 | Alex Miles | Northwestern | 83 | 2 | |

| 11 | Elijah Smith | Emporia/Rutgers-Newark | 74 | ||

| 12 | Devane Murphy* | Rutgers-Newark | 59 | ||

| Peyton Lee | Northwestern | 59 | 1 | ||

| 14 | Nicole Nave | Rutgers-Newark | 57 | 1 | |

| 15 | Ellis Allen | Michigan | 46 | 1 | |

| 16 | Rashid Campbell* | Oklahoma | 37 | ||

| 17 | Ayush Midha | Harvard | 29 | 1 | |

| 18 | George Lee | Oklahoma | 28 | ||

| 19 | Ameena Ruffin | Towson | 25 | ||

| 20 | John Spurlock* | Berkeley | 22 | ||

| LaToya Williams-Green | Emporia | 22 | |||

Other debaters receiving first place votes: Miguel Feliciano, Taylor Brough, Michael Barlow.

All other debaters receiving votes: Alex Parkinson, Alex Pappas, Anna Dimitrijevic, Anthony Joseph, Anthony Trufanov, Beau Larsen, Brad Bolman, Carly Wunderlich (Watson), Charles Athanasopolous , Chris Randall, Corey Fisher, Corinne Sugino, Damyr Davis, Dan Bannister, David Herman, Eric Lanning, Ignacio Evans, Jack Ewing, Jacob Hegna, Jalisa Jackson, James Mollison, Jasmine Stidham, Jason Sigalos, Jeffrey Horn, Joe Krakoff, Joe LeDuc, Jyleesa Hampton, Kaine Cherry, Kenny Delph, Kevin Whitley, Khalil Lee, Kyle Broughton, Layne Kirshon, Marquis Ard, Matt Fisher, Michael Barlow, Miguel Feliciano, Miles Gray, Mimi Sergent-Leventhal, Miranda Ehrlich, Nate Cohn, R.J. Giglio, Ryan Beiermeister, Srinidi Mupalla, Taylor Brough, Vida Chiri, Will Morgan.

Outstanding Team

Georgetown’s Arsht/Markoff celebrating their first NDT win

In this category, 38 different teams received votes, including 11 different first place votes.

Topping the list, by a significant margin, was the team of Georgetown Arsht/Markoff. They were the only team to win two NDTs in the decade, notching an astonishing 33-4 record as a partnership over three tournaments. They also won a Copeland award (interestingly, not in one of the years they won the NDT), as well as a second and third-place finish in the first round rankings.

Overall, the first half of the decade fared more strongly than the second, with the top five spots all being filled by teams who debated from 2010-2015. Indeed, the two teams who won the NDTs that surrounded Geogetown’s second win (Northwestern’s Miles and Vellayappan and Emporia’s Wash and Smith) finished second and third. Meanwhile, the 4th and 5th place finishers (Emory’s Inamullah and Weil and Northwestern’s Fisher and Spies) each only two years in the 2010s at all.

All ten of the decade’s NDT winners (marked in red) finished in the top 15. In fact, only Emory IW and Michigan’s team of Allen and Pappas (#9) broke the top ten without an NDT victory to their name. All ten Copeland winners from the decade are also represented on this list and are marked with an asterisk for each victory.

Two debaters appear twice on this list. Northwestern’s Vellayappan came in at #2 with Miles and then again at #13 with Lee, while Harvard’s Sanjeev appears both with Herman (#8) and with Midha (#11).

Possibly the greatest ‘what if’ on the list is West Georgia’s team of Davis and Feliciano, who finished at #18 despite retiring early in their career. They were certainly among the most talented teams that I had the pleasure to judge and would certainly have appeared on a list of the ten best teams I personally watched over the decade.

A note on vote tabulation: in most cases, the voter’s choice was obvious. But in a few instances, partnership turnover produced some overlapping teams. For example, Quaram Robinson of Kanas received votes for each of her four partnerships. However, by far the most commonly cited partnership was with Katz, so I have listed KR, rather than trying to disaggregate the other scattered votes. However, in the case of Harvard’s teams from the latter half of the decade, I chose the opposite approach. Here, the lion’s share of votes were for the partnership of Herman and Sanjeev, but a significant number also came in in for Sanjeev and Midha, as well as a few votes for Midha and Cooper, with many individual voters listing two or even all three of these teams in their lists. I therefore chose to let each partnership stand alone. If you wish to regard Sanjeev as the connecting force between Harvard HS and MS, the total partnership would have received 130 points and placed slightly higher.

| Team | Points | 1st Place Votes | |

| 1 | Georgetown (Arsht/Markoff)* | 268 | 17 |

| 2 | Northwestern (Miles/Vellayappan)** | 183 | 3 |

| 3 | Emporia (Smith/Wash) | 163 | 9 |

| 4 | Emory (Inamullah/Weil)** | 162 | |

| 5 | Northwestern (Fisher/Spies) | 161 | 1 |

| 6 | Kansas (Katz/Robinson)* | 135 | 1 |

| 7 | Rutgers-Newark (Murphy/Nave) | 107 | 2 |

| 8 | Harvard (Herman-Sanjeev)* | 101 | 1 |

| 9 | Michigan (Allen/Pappas) | 96 | |

| 10 | Kentucky (Bannister/Trufanov)* | 81 | |

| 11 | Harvard (Midha/Sanjeev)* | 61 | 1 |

| 12 | Harvard (Bolman/Suo) | 56 | |

| 13 | Oklahoma (Campbell/Lee) | 53 | 1 |

| Northwestern (Lee/Vellayappan) | 53 | ||

| 15 | MSU (Lanning/Wunderlich) | 50 | |

| 16 | Northwestern (Beiermeister/Kirshon)* | 29 | |

| 17 | Towson (Johnson/Ruffin) | 28 | |

| 18 | Michigan (Krakoff/Morgan) | 27 | 1 |

| West Georgia (Davis/Feliciano) | 27 | ||

| 20 | Loyola (Ewing/Mollison) | 20 | |

| Berkeley (Muppalla/Spurlock) | 20 | ||

| Oklahoma (Giglio/Watts) | 20 |

Other teams receiving first place votes: Harvard Cooper/Midha.

All other teams receiving votes: Berkeley Sergent-Leventhal/Wimsatt, Georgetown Knez/Louvis, Georgia Agrawal/Ramanan, Gonzaga Kanellopoulos/Moczulski, Harvard Cooper/Midha, Harvard Jacobs/Parkinson, KCKCC Casas/Nave, Liberty Byram/Chiri, Oklahoma Chiles/Yahom, Rutgers-Newark Randall/Smith, Towson Thomas/Whitley, UMKC Fisher/Joseph (AT), University of Central Oklahoma Hilligoss/Stidham, UNLV Gomez/Horn, Vermont Brough/Lee, Wake Forest Athanasopolous/Sugino.

Outstanding Coach

Georgetown celebrating with their coach, Jonathan Paul

Voters were asked to rank their top five coaches. 41 individuals received votes, with 14 different first place selections.

Once again, the voting produced a runaway winner, with Jonathan Paul receiving more first place votes than the next four challengers combined. It’s not hard to understand when you consider that Georgetown went from not qualifying for the NDT in 2007 to clearing a team in 2011 to four final round appearances and two victories over the rest of the decade. Of course, the last of those appearances came under the tenure of Mikaela Malsin, who also received votes. Georgetown has certainly been blessed.

Finishing a strong second was Amber Kelsie. Unlike most of the others on this list, who have been firmly entrenched at a single (long-dominant) school, Kelsie spent time coaching at Towson, Pittsburgh, Wake Forest, and Dartmouth. The votes for her therefore represent not only top-level success (though her teams have certainly had plenty), but also a wider commitment to the activity as a whole.

Rounding out the top five were Jeff Buntin at Northwestern, Scott Harris at Kansas, and the team of Dallas and Sherry at Harvard. Each ushered multiple teams to the late elimination rounds throughout the decade.

Tabulation note: as with the votes for outstanding team, there was some occasional overlap, with voters focused more on a coaching team than a single individual. The only case where I simply combined a pair was the Harvard duo of Dallas Perkins and Sherry Hall. Most voters who mentioned one also included the other. And having been lucky enough to work with them for a season, I know firsthand how collaborative they are. It felt silly to try and separate their contributions.

The other most prominent cases were the Northwestern and Michigan squads, where Buntin/Fitzmier and Kall/Heidt received some double votes. Scott Harris and Brett Bricker from Kansas also received a handful of combined votes. These were far less common, however, so I simply chose to count a vote which mentioned both as a vote for both individuals and tabulate their points independently.

|

Coach |

Points |

1st Place Votes |

|

|

1 |

Jonathan Paul |

83 |

14 |

|

2 |

Amber Kelsie |

49 |

4 |

|

3 |

Jeff Buntin |

48 |

3 |

|

4 |

Scott Harris |

45 |

3 |

|

5 |

Dallas Perkins and Sherry Hall |

31 |

1 |

|

6 |

Adrienne Brovero |

23 |

1 |

|

7 |

Ryan Wash |

19 |

1 |

|

|

Rashad Evans |

19 |

|

|

9 |

David Heidt |

18 |

|

|

Shanara Reid-Brinkley |

18 |

3 |

|

|

Dave Arnett |

18 |

3 |

Other coaches receiving first place votes: Dan Fitzmier, Aaron Kall, James Mollison, Matt Moore, and LaToya Green.

All other coaches receiving votes: Aaron Kall, Brett Bricker, Carlos Astacio, Casey Harrigan, Dan Fitzmier, Dave Stoecker-Strauss, Ed Lee, Edmund Zagorin, Ignacio Evans, Jackie Massey, James Herndon, James Mollison, Jarrod Atchinson, Jillian Aleja, Jonah Feldman, Justin Green, Ken Strange, Kevin Hirn, LaToya Green, Mathew Petersen, Matt Moore, Mikaela Malsin, Neil Burch, Rashad Evans, Ryan Galloway, Sam Mauer, Sean Kennedy, Tiffany Dillard-Knox, Travis Cram, Willie Johnson, Will Repko.

Outstanding Judge

Voters were asked to rank their top five judges. 61 individuals received votes, with 15 different first place selections.

The clear favorite was Adrienne Brovero, who appeared on over a third of the ballots, an incredible achievement given the wide range of highly qualified judges, and the idiosyncrasies that go into identifying what counts as ‘best’ in this category.

Finishing 2nd and 3rd here were Scott Harris and Amber Kelsie, who share the impressive feat of being the only two individuals to appear in the top five of both the coaching and judging categories. Rounding out the top five were LaToya Green and John Turner, who narrowly edged out the field to claim a space at the top.

Interestingly, only two individuals appear on both this list and the list for the 2000s: Will Repko and Ryan Galloway.

|

Judge |

Points |

1st Place Votes |

|

|

1 |

Adrienne Brovero |

52 |

7 |

|

2 |

Scott Harris |

34 |

6 |

|

3 |

Amber Kelsie |

23 |

2 |

|

4 |

LaToya Green |

20 |

2 |

|

5 |

John Turner |

18 |

1 |

|

|

David Heidt |

18 |

3 |

|

|

Will Repko |

18 |

|

|

8 |

Kevin Hirn |

17 |

|

|

|

David Cram Helwich |

17 |

|

|

10 |

Brett Bricker |

15 |

1 |

|

Ryan Galloway |

15 |

1 |

Other judges receiving first place votes: Shanara Reid-Brinkley (2), Teddy Albiniak (2), Geoff Lundeen, Sarah Lundeen, Allison Harper, Courtney Schauer, David Heidt, Patrick Kennedy, Brian McBride.

All other judges receiving votes: Adam Symonds, Aliyah Shaheed, Allison Harper, Becca Steiner, Brian Delong, Brian Manuel, Brian McBride, Calum Matheson, Carly Wunderlich, Casey Harrigan, Courtney Schauer, Darron Carrol, Dave Strauss, David Heidt, Deven Cooper, Eric Morris, Gabe Murrilo, Geoff Lundeen, Greta Stahl, Heather Walters, Ignacio Evans, James Herndon, Jarrod Atchison, Jeff Buntin, Jeff Roberts, Joe Krakoff, Joe LeDuc, Jyleesa Hampton, Kevin Whitley, Leah Moczulski, Lindsey Shook, Marquis Ard, Matt Moore, Michael Hester, Mikaela Malsin, Nate Cohn, Patrick Kennedy, Phil Samuels, Philip DiPiaza, Ryan Wash, Sarah Lundeen, Sean Kennedy, Shanara Reid-Brinkley, Stephen Weil, Taylor Brough, Teddy Albiniak, Tiffany Dillard-Knox, Travis Cram, Warren Decker, Whitney Brown, Will Mosley-Jenson, Willie Johnson.

Best Topic

The broad theme here was plurality of opinion. Nine of the ten topics received at least one first place vote, with the roughly half finishing fairly close to one another in the middle. However, most voters did seem to agree that the Executive Authority and Democracy Assistance topics were the least favored, while there was a relatively clear top three in Nuclear Weapons, Climate, and Military Presence.

But the first-place finish for the nuclear topic is actually even more impressive than it looks. Due to an error on my part, voters were not provided with a list of the topics and by the time many voted, they were well into the 2019-2020 Space topic. As such, a few voters included Space and left the Nuclear topic out. For the Nuclear topic to still finish first despite the missing votes suggest that it was in fact pretty heavily favored.

On the bottom, the Executive Authority topic was generally not well received, finishing second to last. It was also the only topic to not receive a single first place vote. But it still finished ahead of the Democracy Assistance topic, which finished in last place by a decent margin.

Two sidenotes: First, since a number of voters ranked the current Space topic, we got a sneak peak of its favorability ratings, or rather its unfavorability ratings. Only time will tell, but it looks like there’s an early frontrunner for least favorite topic of the 2020s. Second, one voter identified “impeach/remove” as the best topic of the decade, even though it was not selected.

|

|

Topic |

Points |

1st Place Votes |

|

1 |

Nuclear Weapons (2009-2010) |

160 |

7 |

|

2 |

Climate (2016-2017) |

159 |

3 |

|

3 |

Military Presence (2015-2016) |

157 |

6 |

|

4 |

War Powers (2013-2014) |

141 |

3 |

|

5 |

Energy (2012-2013) |

128 |

1 |

|

6 |

Health Care (2017-2018) |

124 |

1 |

|

7 |

Legalization (2014-2015) |

109 |

2 |

|

8 |

Immigration/Visas (2010-2011) |

104 |

1 |

|

9 |

Executive Authority (2018-2019) |

80 |

0 |

|

10 |

Democracy Assistance (2011-2012) |

68 |

1 |

Best NDT Hosts

Voters generally agreed on their four favorite NDT hosts, with Weber, Minnesota, Kansas, and Wichita each finishing very close to the top. Iowa just barely edged into the top five, but the gap between 5th and 10th was fairly small.

|

Host |

Year |

Points |

|

|

1 |

Weber |

2013 |

160 |

|

2 |

Minnesota |

2019 |

158 |

|

3 |

Kansas |

2017 |

150 |

|

4 |

Wichita |

2018 |

141 |

|

5 |

Iowa |

2015 |

111 |

Best Regular Season Hosts

This category produced the single biggest runaway winner, with Wake Forest claiming nearly half of the available votes. They certainly run a good tournament, and the people have made clear that they appreciate the good work. Apart from Wake, a few of the other traditional majors received support, as did quite a wide range of others.

|

Host |

Votes |

|

|

1 |

Wake Forest |

15 |

|

2 |

Northwestern |

4 |

|

Harvard |

4 |

|

|

4 |

Kentucky |

2 |

|

Weber |

2 |

|

|

6 |

Dartmouth |

1 |

|

Fullerton |

1 |

|

|

Liberty |

1 |

|

|

Rutgers-Newark |

1 |

|

|

Indiana |

1 |

|

|

Texas |

1 |

|

|

Gonzaga |

1 |

In Memoriam

Over the last decade, the debate community lost far too many of its key historical figures. I can’t possibly hope to discuss everyone who was taken from us, but I will try in this space to identify at least a few who gave so much—especially those who have contributed as coaches. By its very nature, debate is a transitory activity. Every four years an entirely new set of debaters arrive, rise to great heights, and then move on. But there are a few who stick around, who form the institutional memory that ties generations together. This is the chance to celebrate those titans, to reveal just a little bit about their lives and their accomplishments.

Ken Strange

[prepared by John Turner – Ken’s student, colleague, and successor in charge of the Dartmouth Forensic Union]

Ken Strange devoted his life to coaching debate and fostering a debate community committed to in-depth research, well-reasoned argument, and good faith competition. For Ken, the NDT served as both the epitome and embodiment of these ideals. Though Ken’s impact on debate is impossible to fully measure, his legacy includes the many students he coached at the University of Iowa, Augustana College, Dartmouth College, and Wake Forest University alongside the thousands of students who attended the Dartmouth Debate Institute. For every one of those students Ken held both high standards and high hopes. Their testimony across myriad memorials illustrated his fierce competitiveness and passion for improvement alongside his compassion and kindness for all those hoping for their opportunity to debate.

Ken’s squads qualified enough teams to the NDT to hold more than an entire NDT among themselves. His coaching achievements with the Dartmouth Forensic Union from 1980-2015 included winning three National Debate Tournament Championships, five NDT 2nd places, and nine NDT 3rd places. His peers selected him the coach of the decade for the 1980s, reflecting Dartmouth’s semifinals or better showing at every NDT that decade save two. In a coaching feat that may never be equaled, Dartmouth teams won at least one elimination round at the NDT every single year from 1980-2009. He set the standard for a Director of Debate contributing comprehensive research, guiding strategy discussion, and driving argumentative innovation. He produced winning strategies across all five decades of his coaching career.

Ken’s judging displayed his love of argument and his appreciation for the hard work of others in the debate community. In another record unlikely to be equaled, he was voted one of the top five judges in the nation for the 70s, 80s, 90s, and 2000s. No one doubted Ken’s thoroughness in reaching a decision or his commitment to rendering a fair and helpful critique.

Everyone who spent time with Ken encountered his legendary laugh and terrific temper. No one could forget the consequences of disappointing Ken, or the fact that he would be the first to share a joyful story after a memorable blowup. Ken’s retirement speech contained no mention of his own accomplishments as he chose instead to provide an impressive recitation of the foibles of generations of Dartmouth debaters. He treated his program and community as family and clearly relished his life’s work.

Ken refused to say “the NDT.” Ever insistent on word economy, he dropped the article in favor of simply “NDT.” Ken, NDT owes you a great debt of gratitude and your many friends, colleagues, and debaters mourn you.

Ken, celebrating an NDT victory and first place Copeland finish with his team of Ara Lovitt & Steven Sklaver.

George Ziegelmueller

George Ziegelmueller was a professor of communication and debate coach from 1957 to 2006 where he led Wayne State debaters to hundreds of championships in the college debate circuit. Under his direction, Wayne State was established as one of the most successful programs in the nation. During the 1999 National Debate Tournament, the George Ziegelmueller Award was created to recognize Professor Ziegelmueller for his over 30 years of excellent coaching, timeless commitment to the activity, and numerous contributions to the forensics community. The George Ziegelmueller Award is presented annually at the National Debate Tournament to a faculty member who has distinguished himself or herself in the communication profession while coaching teams to competitive success.

Frank Cross

Professor Frank B. Cross of the University of Texas Law and Business Schools was a national debate champion at the University of Kansas (1976), Harvard Law School graduate, former practicing attorney, and long-time professor and scholar in Austin. By general acclamation, he was one of the best debaters of the 1970s, widely referred to as the best 2N of his era. His partner Dr. Robert Rowland wrote the following: “Frank B. Cross demonstrated that an ordinary kid from Kansas could through hard work go on to become one of the best KU debaters of all time and win the NDT, excel at Harvard Law School, work at an elite Washington law firm, and teach with distinction as a named professor at both the School of Business and the Law School at the University of Texas. His success as a famous legal scholar came as no surprise to anyone who ever debated him. He was always the brightest person in any room he occupied, but wore that gift with grace and wit. We mourn the loss of one of the greatest debaters of his generation, but celebrate the life of a dear friend.”

1976 NDT champions Frank Cross and Robin Rowland compete at the Heart of America Debate, April 1976. Image courtesy of University Archives, Spencer Research Library, KU

Alfred “Tuna” Snider

Alfred “Tuna” Snider attended Brown University, where he was a top-ranked national debater. He earned a master’s degree in rhetoric and public address from Emerson College and his doctorate in communication studies, personal and social influence, from the University of Kansas. He then moved on to direct the Lawrence Debate Union at the University of Vermont for the next forty years. Anyone who grew up in debate over the past three decades did so in Tuna’s shadow. I remember my own early ventures online to learn about debate and discovering his Debate Central website. Tuna was a tireless advocate for debate and critical engagement, a campaign he took all across the world. From the University of Vermont’s statement on his death: “Snider traveled to 45 countries on nearly every continent to advance the art of debate—in developing nations, under communist regimes and in war-torn territories—including Serbia, Iraq, Pallestine [sic], Botswana, Afghanistan and Chile. Since 1984, he served as director of the World Debate Institute.” Dr. Snider consistently promoted debate as a vital instrument of democratic engagement. One of his favorite slogans was “replacing weapons with words,” and he truly lived that ideal. According to Jairus Grove: “Tuna Snider is a planetary scale phenomena. We would need google earth to show how many debaters, debate programs, thinkers, activists, carry his passion with them.”

Holt Spicer

Holt Spicer was truly one of the giants of the early years of the NDT. He and his partner shared the two top speaker awards in 1951 and 1952, winning the tournament both years. You will find his name littered through this document, with records for individual and team wins, multiple NDT victories, and as one of the contestants in a debate across generations in 1991. After graduated from Redlands, Spicer served as the debate coach at Missouri State University from 1952 until 1965. In 1965, Spicer became the head of the Department of Communication, but continued to remain involved in the team over the following decades. Even after his retirement in the 1990s, Spicer remained engaged with the team, including serving on the search committee that found current coach Eric Morris. The Missouri State debate team continues to bear his name.

Neil Berch

Neil Berch served as a West Virginia University associate professor of political science since 1992 and as coach of the WVU Debate Team since 1997. Samantha Godbey, his longtime assistant, said the following: “He was a great educator and mentor. The debate team and the University are really going to miss him. His main priority was the students – he wanted to make sure every student had equal opportunity and equal access and he also wanted to inspire them to be better people.” Christy Webster Dunn: “Neil fought a valiant battle for almost a decade and I was in constant awe of his tenacity and resourcefulness. He was a uniter, a mediator, a right-fighter and an all around brilliant man.”

Arnie Madsen

Arnie debated for Buffalo High School in Wyoming and then debated for Al Louden at Northwest Community College and then went on to complete his career as a debater at Eastern Montana College. He earned a master’s degree in Communication Studies from Wake Forest University, and then taught and coached debate at Illinois State University. He earned his PhD from Northwestern University in Communication Studies, and then taught and coached debate at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Northern Iowa. He served as NDT Committee chair for several years. He hosted the NDT at Illinois State, and worked in the NDT tabroom for over a decade. Several people commented that when Arnie was working in a tabroom, he was the person they would send out to ask people to judge extra rounds because no one could say no to him. In addition to his contributions within the activity, he was also an active scholar, publishing regularly in argumentation and rhetoric, and touching the lives of many students and colleagues.

Chester Gibson

Chester received his BA, MA and PhD all from the University of Georgia. He began coaching debate at West Georgia College in 1971 where he served as the director of debate for 25 years. As Michael Hester said, “he is the reason you know anything about West Georgia debate… WG Debate had functionally been a student club for most of its then-40+ year existence. Within three years of his arrival, West Georgia had earned an NDT First Round, and within his first 12 years as Director, West Georgia had reached the NDT semifinals, had a 2nd place speaker at the NDT, a 2nd place ranked FRALB team… It is not an exaggeration to say that the last half-century of West Georgia being one of the top debate programs in the nation – every trophy, every champion, every success – Chester Gibson is responsible for it. I was the first member of my family to go to college – because Dr. Gibson offered me a free ride, which was the only way I was going to afford any school. I became the DoD at West Georgia College in 1995 because Dr. Gibson pulled me aside my senior year and told me that if I would go get a master’s, he’d hire me to coach the team.” Chester hosted the NDT twice. He qualified a team for the NDT 22 consecutive years and earned a First Round bid at least 8 times. He served as chair of District 6 for 13 years and helped to secure the funding for the Copeland Award. He also personally funded the Ovid Davis Award – the watch given to the coach of the NDT champions.

Skip Eno

Skip was the Director of Debate at UT San Antonio from 1982 until his passing in 2017. During that time the UTSA debate team earned numerous awards including regional and national championships. He earned many personal accolades including coach of the year by the Southern Speech Association and was named an All-Star Coach by the CEDA South-Central Region in 1996. Skip was also the recipient of the Jeff Jarmon Person of the Year Award in 2016. According to Kate Richey, one of his debaters: “Skip lead a UTSA debate team comprised of weirdos, burn-outs and adult students on their third second-chances. … I was working double shifts at … restaurants, babysitting rich people’s children, and taking a full course load+ to get through school. Finding time for debate wasn’t easy, but no matter what, Skip wanted us at tournaments and he did everything in his power to make that happen. …. He could argue with you until he was blue in the face, but he would also argue for you with his every breath. Skip believed in his debaters when nobody else would and he saw the best in the most difficult people. … Skip loved to talk, loved to argue, loved to genuinely laugh.”

Bruce Daniel

Bruce Daniel was a debate coach at West Georgia College. His debate career has D3 roots, having attended Southwest Missouri for his bachelor’s and was in the doctoral program and Kansas. In between he earned his master’s at Eastern Illinois. While debate coach at WGC, Bruce coached teams to the NDT every year, including First Round teams.

Michael “Bear” Bryant

Michael “Bear” Bryant was the longtime coach at Weber State, and a famous (and enthusiastic) presence in the early days of online national debate communication. According to Doug Dennis, one of his former debaters: “Debating for him wasn’t always easy – in fact, it was rarely easy – debating for Bear was hard because he had expectations for you, and it always seemed, at least for me, those expectations were well beyond my reach and rarely did I meet those expectations, which was simultaneously infuriating and motivating…but he never stopped caring. That’s the part most people never got to see. He cared about his debaters in a way most can’t or won’t.” Bear also took that passion out into the world. He was a strong supporter of the Southern Poverty Law Center, and devoted tireless efforts to fighting against racism both online and in person. In the words of Ken DeLaughder, “he was full of piss and vinegar, but his heart was also filled with love.”

Jack Kay

Dr. Jack Kay, twice graduated from Wayne State University, championed student academic success and the study of communication throughout a thirty year career in higher education. He was a member of the nationally recognized Wayne State debate team and coached the team as a graduate student. A decade later, he returned to his alma mater as a professor of communication and chair of the Department of Communication. In his later career, he also served in several administrative roles at Wayne State, including dean and provost.

Dave Matheny

Dave “Pops” Matheny received his PhD in Rhetoric from the University of Oklahoma. He taught and coached debate at Texas Christian University and later retired from Emporia State University. He was past-president and inducted into Hall of Fame at Kansas Speech Communication Association. His two daughters also both debated in college and coached for a while. He served in the United States Army during the Korean Conflict, stationed at the Panama Canal Zone. According to one of his former students: “When you got past the thunderous timbre of his voice and towering presence, I found an educator that took the time to care, identify talent and offer opportunity simply because it was the right thing to do. I’m eternally grateful for that.

Tom Kane

Tom Kane taught at the University of Pittsburgh from 1965 until his retirement in 1999, coached the University of Pittsburgh to the National Debate Championship in 1981, and was twice named National Coach of the year by Emory University (1973) and Georgetown University (1981), named Honorary Citizen of Texas in 1982 for his work with high school debaters at Baylor University.

Al Johnson

James Al Johnson was the Director of the National Debate Tournament from 1990-1992. He was former professor of economics, registrar, and debate coach at Colorado College, was named outstanding forensics educator by the American Forensics Association. During his nearly 50-year career at CC, Johnson directed three national debate tournaments, co-founded the Cross Examination Debate Association in 1972, and founded the National Parliamentary Debate Association in 1993.

Debate Topics

The early NDT’s had a national topic available to them, however, the West Point Debating Society took considerable liberties with that process. This was not unusual, since debate prior to the NDT was largely regional in nature, with the exception of the Speech Fraternities National Tournaments, which involved all types of events and large convention settings. In 1949 the national topic was, Resolved: That the Federal Government should adopt a policy of equalizing educational opportunity in tax-supported schools by means of annual grants. In January of 1949 Lt. Col. Chester L. Johnson, Officer-in-Charge of the Debate Council at West Point, wrote the regional chairpersons the following letter:

“I am writing to solicit your advice concerning a major question which has been raised concerning this year’s West Point Tournament (April 21-24).

We are somewhat concerned about using the Federal Aid to Education topic in this year’s tourney.

There exists a 50-50 possibility that within the next three and a half months the Congress may render this topic sterile. Whether or not enacted legislation would fit the Need, be Practical, and Desirable, it would raise hob with our debating–not that fait accomplis are not inherently debatable but because of the psychological atmosphere that such governmental action would generate.

Were we to choose an alternate question as a safeguard it should be settled prior to 1 February.

I should, therefore, appreciate your considered opinion first as to the general proposal as to whether or not a subject other than the present national question should be used at West Point, and second your preferences among the following questions:

(1) Resolved: That a system of pre-paid medical insurance be adopted by our Federal Government

(2) Revolved: That the Federal Government should adopt a policy divided towards government ownership and operation of the steel industry and the major sources of energy.

My political prognosticator assures me that a medical insurance program is not as likely of adoption at an early date as Federal Aid to Education. The second question of course raises even more clearly the ghost of socialism. I have not suggested a foreign policy question because the dynamics of world relationship move with such speed today that even the more general topics might jump the tracks.”

Thus, after several exchanges between West Point officials and the Regional Committees, it was decided that the topic to be used at the 1949 National Tournament would be; RESOLVED: That the Federal Government should adopt a system of pre-paid medical insurance.” Perhaps inspired by their “topic changes” in 1949 the West Point Debating Society decided upon even more innovative changes for the 1950 Tournament. My research over the years has enabled me to locate some invaluable sources of information. After the 1950 NDT West Point began publishing a post book which described, in detail, the previous NDT. What follows is a most interesting review of how the tournament was organized and structured from the 1950 West Point National Invitational Debate Tournament and Brief History of Debating at West Point. Note how the topics varied throughout the tournament.

“As in the past years, those participating in this year’s tournament at West Point–debaters, coaches, and invited judges–were guests of the West Point Debate Council. Meals were provided male guests in the Cadet Mess Hall, while female guests were fed at the Officer’s Mess. Lodging was provided male students in the Visiting Athletic Team rooms. Female and faculty personnel were guests of officers’ families on the Post. No fees were charged participants for food, lodging, or administrative expenses–these being met by the normal revenues of the Debate Council, cadet dues and an appropriation from athletic funds. Debate groups interested in coming to West Point experience one major item of expense–transportation to and from West Point.

During the past four years we have been interested in noting the ingenuity several “poverty stricken” groups have used in overcoming the cost of transportation obstacles. Those who were unable to

budget normal revenue either succeeded in enlisting further appropriations from Student council funds or sought aid from extra-mural sources. Thus, newspapers, bar associations, business men’s clubs, and interested alumni have voted affirmatively on a proposal to underwrite travel costs.